1.0 Introduction

In the past few decades, the academic knowledge of uncertain and information in economics has been developed very fast. People will face uncertainty when they do not know something about the world. For instance, no body could accurately predict the consequences of their actions. It shows that people lack complete information. Hence, in order to reduce uncertainty or ambiguity, people have to try their best to obtain information. From the perspective of economics, the economics of uncertainty and the economics of information are two important topics for economists to deal with uncertainty and asymmetric information. The book selected for this review is titled “Introduction to the Economics of Uncertainty and Information”written by Timonthy Van Zandt in Nov 2006. The major contents of the book is quite coherent with my textbook, “the Analytics of Uncertainty and Information”, which introduces very basic uncertainty and information concepts in a simple and easily understandable manner. This book review aims to provide a comprehensive summary of the book, its real-world application and my own reflection about various economics model and conceptions.

2.0 Summary of the Selected Book

The selected book effectively demonstrates how Timonthy manages to deliver the message to target audiences that the economics of uncertainty and information could play an important role in dealing with issues such as safety and health, allowable return on investment, and income distribution. In the introduction section, the author has clearly introduced the concept of uncertainty and information to his readers (Van Zandt, p1). According to his definition, the economics of uncertainty, is referring to the economic situations in which there is uncertainty but everybody has the same information in hand. The economics of information, on the other hand, is about economic situations in which people have asymmetric information(Van Zandt, p1). For instance, when someone is buying life insurance of , it means that he has uncertainty about his flight. The plane may crash halfway. Through buying life insurance, he is transferring this risk to insurance company so he could have financial compensation after unpredictable incident. Insurance company also does not know about the amount of money which has to compensate the insurant. There is a rough approximation agreed between the insurant and insurance company. In this case, it could be observed that both parties have the same information, which is the likelihood that the insurant may suffer from an airplane crash. The author effectively illustrates an example of uncertainty economics here. Economists will be particularly interested in the premiums that the insurance company offers and the amount of insurance fee which insurant has to pay. Under the same context, when an insurnt is applying for a health insurance, he also intends to the transfer the risks to insurance company. But it might be very different from a life insurance as insurant and insurance company tend to have different information. For example, the insurance applicant might know more about his health status. He may know that he has high possibility to have heart attack or other diseases. If the application is successful, insurant might try to increase the chances of having health-related problems, let say, eating oily food, smoking, and so on. In this way, when an insurant is getting unhealthy, he is demanding compensation or reimbursement from the insurance company. However, insurance company could not keep an eye on the daily activities of applicants. Only doctor and the applicant himself know more about his health and physical status. In this sense, even though the insurance company may try its best to investigate whether the applicant lies about his health status before contracting, the insurant may still secretly take high-risk activities as the above-mentioned. Therefore, the concept of economics of information is relevant in this transaction. The insurance company, for instance, has to estimate the deductibles in order to compensate the asymmetric information.

2.1 Expected Utility Theory

Both my textbook and the selected book have focused on introducing and explaining the expected utility theory to target readers. The author of “Introduction to the Economics of Uncertainty and Information” starts to introduce utility theory in chapter 2.5 (Van Zandt, 2008). He has proposed a very interesting definition for utility theory. He states that if Preference ![]() over lotteries L could satisfy expected-utility maximization if there is a utility function u: Z → R such that P

over lotteries L could satisfy expected-utility maximization if there is a utility function u: Z → R such that P ![]() Q (P and Q are any lotteries). If and only if

Q (P and Q are any lotteries). If and only if

The author insists that the utility function of u: Z → R is highly relevant. It could ensure that each outcome lottery will produce a utility value. Without this function, let say, Z = {death, $100}. The author points out that the outcome does not make sense because it is difficult to take an average between death and $100. Based on definition above, the expected utility of P is denoted as

So within the utility function, u: Z → R, a person tends to prefer over outcome lottery with the highest expected utility.

Based on the expected utility theory, the famous von Neumann-Morgenstern theorem could also be well explained. By definition, von Neumann-Morgenstern utility theorem states that a decision-maker will face risky outcomes under certain independence or continuity axioms. He or she tends to maximize the expected utility value over outcome lotteries at specific point in the future. In mathematical notation, the Von Neumann-Morgenstern theorem could be expressed as:

If ![]() satisfies the Independence and Continuity Axioms (such as axioms of rational behaviors), the theorem will satisfy expected utility-maximization (van Zandt, p27).

satisfies the Independence and Continuity Axioms (such as axioms of rational behaviors), the theorem will satisfy expected utility-maximization (van Zandt, p27).

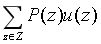

The reason why I put an emphasis on illustrating the theorem is that it is closely associated with the concept of risk aversion. As shown in the diagram below, U(W) is a von Neumann-Morgenstern utility index that reflects how the individual feels about each value of wealth. The curve is concave. It reflects that the marginal utility value will diminish when the overall wealth or income of a person is increasing.

Fig 1: Risk Aversion

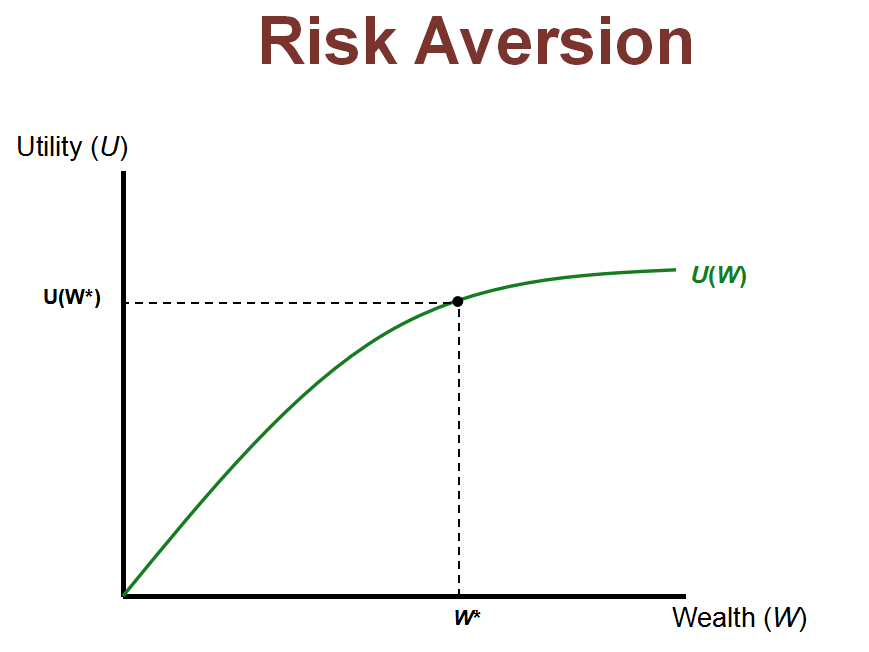

Suppose that Suppose that W* is the individual’s current level of income, then the expected utility value will be U(W*). If a person is offered with two fair gambles, 50% of winning or losing $h or $2h, the risk aversion function will be something as follows,

Fig 2: Risk aversion function for two fair gambles

The expected utility function of the first fair game is,

Uh(W*) = ½ U(W* + h) + ½ U(W* - h)

And the expected utility function of the second gamble is,

U2h(W*) = ½ U(W* + 2h) + ½ U(W* - 2h)

So as shown in fig 2, it is obvious that

U(W*) > Uh(W*) > U2h(W*)

Hence, based on the equation above, it could be concluded that the person will prefer the current expected value associated with his current wealth. But he will prefer a small gamble ($h) over a larger one. The significance of these conclusions is that a person might wish to pay a certain amount of money to avoid participating a gamble. For instance, many people have chosen to purchase insurance packages to avoid gamble or potential risks.

3.0 Real-World Application of Expected Utility Theory

In fact, expected utility theory, Von Neumann-Morgenstern utility theorem and risk aversion concepts could be connected to the world’s economy. Gandelman and Rubén (2015, p3) manage to measure the coefficient of relative risk aversion for 75 countries which are further divided into two categories, including both developed and developing countries. The data are cited from the reports released by the Gallup World Pull. They discover that the coefficient of the relative risk aversion is closely related to the log utility function.

At an individual level, it seems that one’s expected utility value could be estimated through expected utility theory. Individual’s risk attitudes and economic decisions such as precautionary savings, investment in human capital, entrepreneurship, investment in real estates, etc, may affect a country’s economic growth and development outcomes as a whole. However, the previous studies are relatively focusing on investigating how individual’s decision-making process or risk attitudes might be affected by gambles or outcome lotteries. Very few associate the theory and various concepts with country’s context. The first model to measure the risk aversion at a country level is proposed by Hansen and Singleton (1982, p249). They manage to interpret the risk aversion through consumption-based capital asset pricing model (CAPM). The utility function in measuring the risk aversion proves to be a significant failure simply because it is rather difficult to predict the consumption growth.

Alternatively, Layard et al. (2008, p1846) has proposed another more reliable method, called Constant Relative Risk Aversion (CRRA) utility function based on happiness data of different countries. Layard et al. (2008,p1846) discovers that the happiness data is closely related to marginal utility of income. So they conclude that the marginal utility of income corresponds to relative risk aversion. It is coherent with the Von Neumann-Morgenstern utility theorem and risk aversion concepts illustrated in section 2.

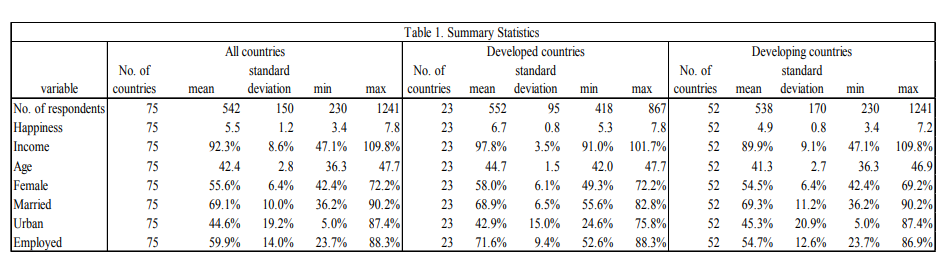

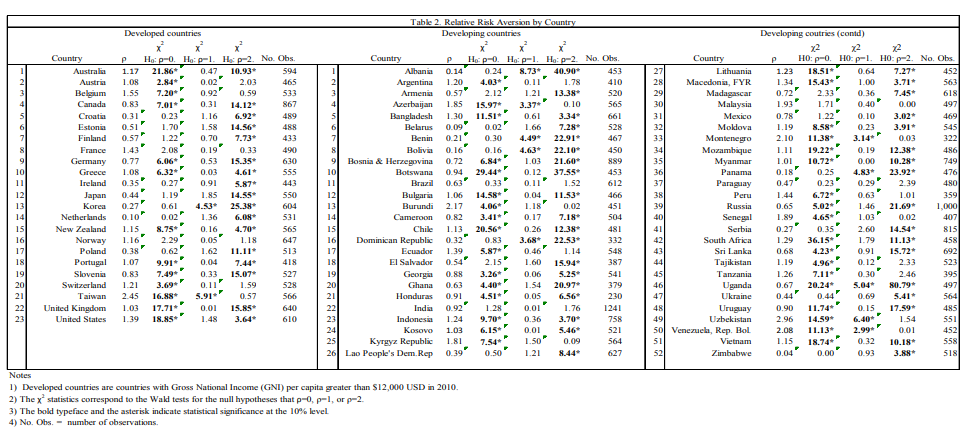

Gandelman and Rubén (2015, p4) have conducted a secondary research by citing data from the Gallup World Poll including 52 developing countries and 23 developed countries. The economics variables are not limited to consumption, happiness and so on. It intends to identify the national differences of relative risk aversions reflected by various factors as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Sampling of cross-country differences in terms of different economics factors

Source credit: Gandelman and Rubén (2015, p13)

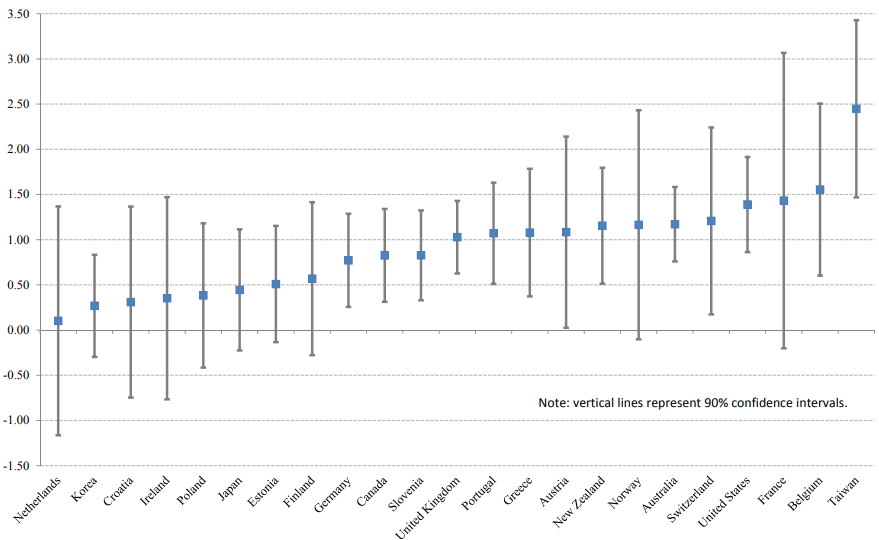

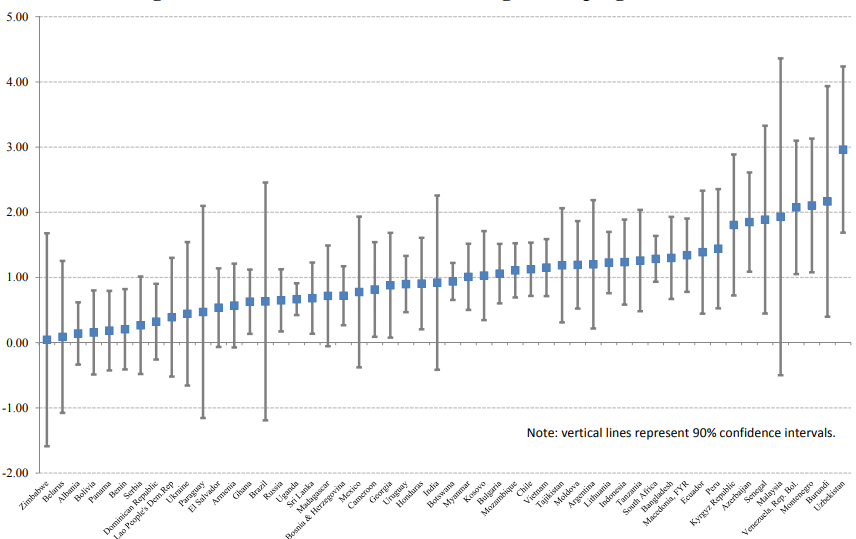

Through applying expected utility theory, the two researchers manage to calculate the risk aversions among developed countries and developing countries shown in fig 4 and fig 5.

Source credit: Gandelman and Rubén (2015, p13)

Fig 4: Relative Risk Aversion among developed countries

Source credit: Gandelman and Rubén (2015, p13)

Fig 5: Relative Risk Aversion among developing countries

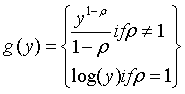

In fact, the method of calculating relative risk aversion of different factors is in accordance with the knowledge introduced in the selected book. The general utility function in the above-mentioned research is

u = U(y, x) = α + γg(y)+ β

Where α and β are column vector of coefficients that controls x. g(y) is the Constant relative risk aversion function (CRRA). The expected utility value of an individual is denoted as u = U(y, x). x denotes the individual characteristics. y presents the income of an individual. Hence, the CRRA could be further expressed as

ρCorresponds to the Arrow-Pratt coefficient of relative risk aversion. Based on the expected utility theory and CRRA, an individual’s expected utility and risk attitudes at a country level could be easily understood. Happiness, for instance, could be denoted as h, so based on the utility theory,

hi = U(y, x) = α + γg(yi)+ xiβ + vi

i = 1, 2,...,n which is the individual indices. α and β are column vectors same as above. hi is the happiness index, vi is the error terms which is independent of individual’s expected utility. Through this method, the relationship between an individual’s happiness, expected utility value and risk aversion could be effectively calculated.

The risk aversions of 75 countries could be expressed in table 2 below,

Table 2: CRRA by country

Source credit: Gandelman and Rubén (2015, p13)

In fact, researchers have discovered that the average risk aversion value among developed country is 0.92 whereas developing country is 1.00. So it implies that both developing countries and developed countries display a risk aversion value in vicinity to 1. As the risk aversion is estimated between 0 and 3. The results imply that individuals from majority of countries in the world has low aversion. In other words, they prefer low returns with certain risks instead of high returns with uncertain risks. It shows the risk attitudes in different countries.

From the table 2, through applying the risk aversion conception and expected utility theory, it could also be feasible for me to predict the local people’s risk attitudes toward uncertainty. For instance, in Taiwan, the risk aversion is around 2.45. It shows that people there are willing to bear risks. In fact, it is largely because Taiwanese lose confidence about the local government. They are more willing to find job opportunities in an unknown working environment such as mainland China, even though they know very few about the country. Netherlands for instance has a CRRA value of 0.10. It is because the local economic and political environment is high stable. Residents there tend to be not very risk-bearing.

4.0 Personal Views

Throughout the book, the author does provide very comprehensive, informative and clear definition of various economics concepts by raising meaningful and relevant examples. In fact, based on my own understanding, economics of uncertainty and information will not only apply in one particular economic activity but also in many other disciplines. In labor economics for instance, employees tend to know more about their own capabilities, talents and skills than their employers often do. In this way, employers and employees are having different information. Good employers or leaders can empower employees with more power and fully develop their capabilities and potentials. Economics of uncertainty and information is also relevant in finance. Most of the financial instruments aim to share the risks. Investors actually have uncertainty about their investment and returns. Traders, on the other hand, tend to have more information than investors or shareholders. In the field of sales and marketing, salespersons and marketers have more information about the quality of goods or services than their target customers. Producers will also have more detailed information about their production cost than other major competitors. Thus, it is indisputable that to learn more about economics of uncertainty and information is extremely relevant and meaningful for other interdisciplinary study.

In this book review, to a very large extent, I believe that van Zandt, the author of “Introduction to the Economics of Uncertainty and Information” has managed to deliver his key idea associated with economics of uncertainty and information very clearly to readers. In fact, I am inspired by his explanations and perceptions about the real world applications of this new discipline. I find that van Zandt is really skillful in describing or explaining a theory through his use of diagrams and mathematical expressions. The first part of the book is actually based on the expected-utility theory. He manages to show that people tend to make rational decisions and it might be affected by the stats of nature. The second part of the book is about explaining economics of information. The author has illustrated very clearly about the difference between public and private information. The conclusions derived could be used to explained people’s terminal decisions and market equilibrium. With respect to information asymmetry, the author tries to include the Game theory content in this second edition. By illustrating prisoner’s dilemma, Dvorak keyboard and other cases and supported by clear mathematical expressions, the author makes the concept of Nash equilibrium clearer for readers.

Reference (MLA)

Bikhchandani(2013). The analytics of uncertainty and information. Cambridge University Press.

Gandelman, Néstor, and Rubén Hernández-Murillo. "Risk aversion at the country level." (2015).

Layard, Richard; Mayraz, Guy; and Nickell, Stephen John. “The Marginal Utility of Income.” Journal of Public Economics, 2008, 92(8-9), pp. 1846-57.

Hansen, Lars and Kenneth J. Singleton. “Stochastic Consumption, Risk Aversion and the Temporal Behavior of Asset Returns.” Journal of Political Economy, 1983, 91(2), pp. 249-65.

Van Zandt, T. (2008). Introduction to the Economics of Uncertainty and Information. Oxford.